Scientists show how we can anticipate rather than react to extinction in mammals

Most conservation efforts are reactive. Typically, a species must reach threatened status before action is taken to prevent extinction, such as establishing protected areas. A new study published in the journal Current Biology shows that we can use existing conservation data to predict which currently unthreatened species could become threatened and take proactive action to prevent their decline before it is too late.

"Conservation funding is really limited," says lead author Marcel Cardillo of the Australian National University. "Ideally, what we need is some way of anticipating species that may not be threatened at the moment but have a high chance of becoming threatened in the future. Prevention is better than cure."

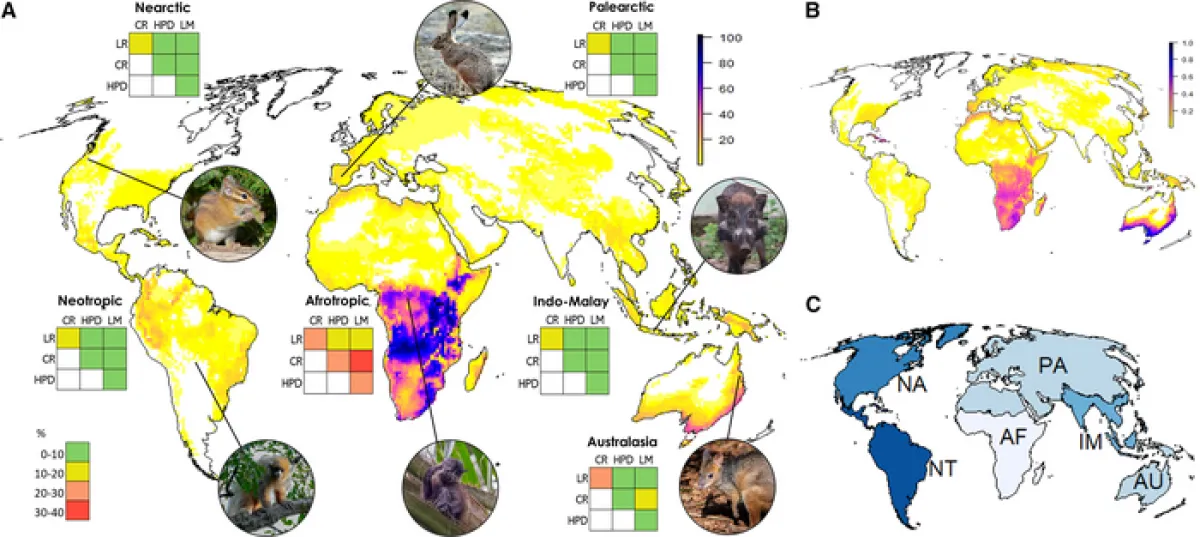

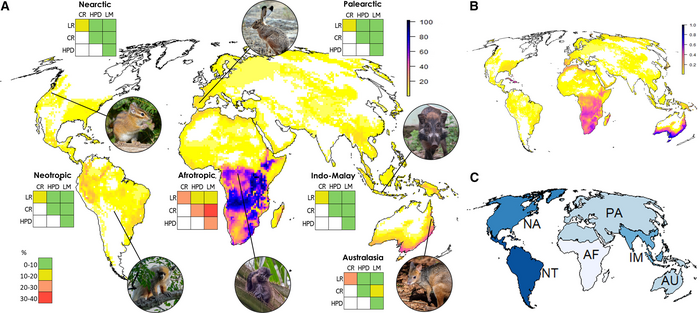

To predict "over-the-horizon" extinction risk, Cardillo and colleagues looked at three aspects of global change – climate change, human population growth, and the rate of change in land use – together with intrinsic biological features that could make some species more vulnerable. The team predicts that up to 20% of land mammals will have a combination of two or more of these risk factors by the year 2100.

"Globally, the percentage of terrestrial mammal species that our models predict will have at least one of the four future risk factors by 2100 ranges from 40% under a middle-of-the-road emissions scenario with broad species dispersal to 58% under a fossil-fueled development scenario with no dispersal," say the authors.

"There's a congruence of multiple future risk factors in Sub-Saharan African and southeastern Australia: climate change (which is expected to be particularly severe in Africa), human population growth, and changes in land use," says Cardillo. "And there are a lot of large mammal species that are likely to be more sensitive to these things. It's pretty much the perfect storm."

Larger mammals in particular, like elephants, rhinos, giraffes, and kangaroos, are often more susceptible to population decline since their reproductive patterns influence how quickly their populations can bounce back from disturbances. Compared to smaller mammals, such as rodents, which reproduce quickly and in larger numbers, bigger mammals, such as elephants, have long gestational periods and produce fewer offspring at a time.

"Traditionally, conservation has relied heavily on declaring protected areas," says Cardillo. "The basic idea is that you remove or mitigate what is causing the species to become threatened."

"But increasingly, it's being recognised that that's very much a Western view of conservation because it dictates separating people from nature," says Cardillo. "It's a sort of view of nature where humans don't play a role, and that's something that doesn't sit well with a lot of cultures in many parts of the world."

In preventing animal extinction, the researchers say we must also be aware of how conservation impacts Indigenous communities. Sub-Saharan Africa is home to many Indigenous populations, and Western ideas of conservation, although well-intended, may have negative impacts.

Australia has already begun tackling this issue by establishing Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs), which are owned by Indigenous peoples and operate with the help of rangers from local communities. In these regions, humans and animals can coexist, as established through collaboration between governments and private landowners outside of these protected areas.

"There's an important part to play for broad-scale modeling studies because they can provide a broad framework and context for planning," says Cardillo. "But science is only a very small part of the mix. We hope our model acts as a catalyst for bringing about some kind of change in the outlook for conservation."

First published by Cell Press/EurekaAlert.